Motorcycle Investor mag

War babies

by Guy 'Guido' Allen

(from Motorcycle Trader magazine #352, circa Oct 2019)

(Ed's note: see the WWII despatch rider video at the end.)

They either got ridden into the ground, or shot at, sometimes both on the same day. Whatever their intended fate, no-one expected these old soldiers to become collectible

It’s one of life’s little principles that there is a wealth of ‘stuff’ in our lives that goes through this weird lifecycle. It starts off as shiny, new and useful, then it progressively becomes worn and outdated. If it doesn’t end up in the tip, one day (decades later) it’s pulled out of a cupboard or shed and once again becomes a treasured possession. The whole classic vehicle movement is based around this idea.

If you were to go out and seek the most extreme version of this whole treasure-to-trash-to-treasure journey, none works better than military motorcycles. These, after all, were the ultimate consumable. Intended to tackle anything from relatively safe behind-the-lines courier work to frontline duty, they were designed to be tough and reliable, but there was absolutely no glamour or sentiment attached. If the engine blew up, no-one repaired it – they just pulled out another from stores, unwrapped it from the grease-paper and whacked it in. If that was too hard, they just gave you a replacement bike and left the old one where it stopped.

Thankfully, for most of recent history military motorcycles have been little more than highly-specialised curiosities, produced in low numbers, which have had little or no impact on the broader market. I say thankfully because the only time that changes is when there is a large-scale warfare. It was World War II (1939-45) which most dramatically expanded the demand for military motorcycles and, as a result, produced some iconic models.

There have been countless variants on the motorcycle theme and you could comfortably fill a substantial book with them. Arguably the most successful - judged either through initial production numbers or the numbers that have survived – is the Harley-Davidson WLA. An incredible 90,000 of these things were produced, about a third of which ended up in Russia as part of the USA’s wartime Lend-Lease effort, where it supplied allies with a huge volume of material.

Look at the thinking behind the development of the WLA and you’ll gain an insight into pretty much every successful military motorcycle. Really, the criteria isn’t rocket science. Whatever you come up with has to be a few things: robust, reasonably simple to use and repair, not too thirsty when it comes to fuel, and built to survive hostile conditions, including off-road use.

Given those criteria, it’s not hard to see how and why single-cylinder trail bikes have become the favoured option for current machines. However if you go back to the 1930s and 1940s, the thinking was a little different. At least some of the bikes had to manage big loads, probably with a sidecar attached. They were in effect acting as an alternative to a light car, or an ATV, before we knew what an ATV was…

Harley’s approach to this was interesting in part because it skipped past its then latest engines to take a giant technological leap backwards. In the late 1930s, the company had access to two premium powerplants, namely the litre-class overhead-valve EL Knucklehead and the 1200 sidevalve used in the UL series. Instead it went for a variant on its tried and tested W-series 750 sidevalve, an engine that remained in production for the Servicar three-wheeler utility vehicle all the way through to the 1970s.

That powerplant was good for 25 horses and ran a mere 5:1 compression ratio (about half what we’d now regard as average). Low compression means lower stress on components, an easier engine to kick over and, most importantly, something that will run even when the fuel quality is dodgy. Breathing was through a re-usable oil-bath air filter.

The engine was matched to a ‘crash’ three-speed gearbox (no synchro) with hand shift and foot clutch. While that sounds nightmarish, it was a pretty standard set-up at the time and you just lived with it. Top speed was about 105km/h.

Suspension was a springer front end with a hardtail rear and a sprung saddle. As for brakes, you had a pair of mechanical drums. The chassis was raised a little for the military models for extra ground clearance. Add in a little gusseting here and there, plus some racks to carry extra gear and there was your military bike.

While the recipe is simple enough, these things had to perform. Commands in various countries were notorious for their punishing testing regimes and rejecting certain models, no matter who they came from. Both BSA (with a variant of the M20) and BMW (with an early R75) got knock-backs and were told to try harder.

So, with the war ending, what happens to these hordes of machines? A lot of them ended up trashed while in service or destroyed and used as landfill after hostilities. You can imagine quite a few may have ended up as ‘souvenirs’ and being quietly squirrelled away in sheds. However vast quantities were sold as surplus.

Now that last group is far more significant in our motorcycling history than many people realise. Some quite famous industry names over the post-war years got their start by buying surplus bikes and turning them into a business. More often than not this was done by civilianising them with a fresh lick of paint (no camo green, thanks) and few bits of trim, then selling them on at a profit. In a market that had been starved of new vehicles during the war years, a tarted-up ex-army bike looked like a damn good option.

Of course these things changed status over time. As the civilian market got back into full swing, they soon looked a bit primitive and out of date, eventually finding somewhere dark to retire – either at a metal recycler or under a tarp in a shed. And now - what’s that saying about everything old being new again?

The very bikes that were probably bought at a surplus auction for a few quid are now very much back on the collector radar. For something like a WLA, you’re looking at around 25-30k for a very well restored one, while the really rare stuff can command a fortune. Who knew that these very utilitarian tools would one day end up being treasured?

(Pics: Harley-Davidson corporate museum)

****

Trusty Trend-Setter

While WWII saw volumes of military motorcycles that were previously unthinkable, the trend began with World War I and went on to ‘make’ the reputations of some manufacturers.

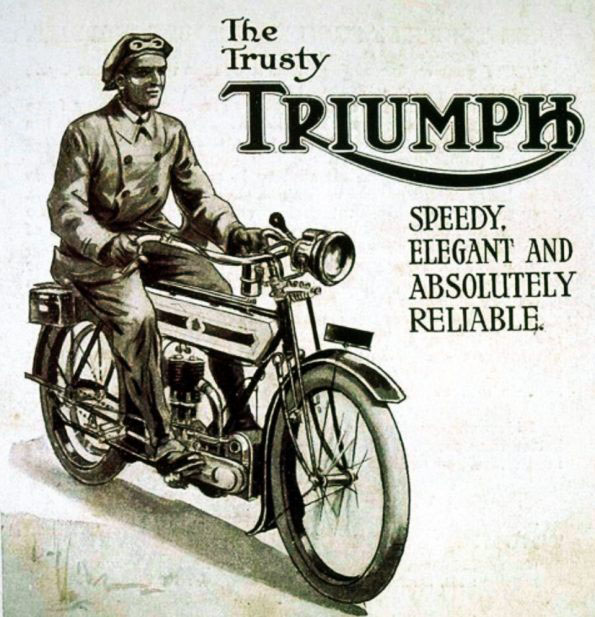

There’s no better example of this than Triumph’s Model H, which was launched in 1915. Running a sidevalve 550cc single powerplant, it was sophisticated for the day in having a three-speed Sturmey-Archer transmission, and a kickstarter instead of pedals. Several thousand saw war use and some 57,000 were made by the end of the model run in 1923 – a huge number for the period.

Triumph’s own advertising referred to it as the Trusty Triumph, which was its popular nickname – though whether the factory or owners came up with the handle is up for debate. Prices for good examples are substantial, as pukka veteren machinery has been doing well in recent years. For example, we've seen a couple of good examples hit the $30,000-plus mark.

****

American oddballs

Both Harley-Davidson and Indian produced huge volumes of V-twins (750 WLAs and 750 or 500 Scouts respectively) for the war effort and both went a little outside their comfort zones at the time by producing one-off models that never saw light of day after WWII.

For H-D it was the XA (pictured above), loosely modelled on the BMW and Zundapp boxer twins of the time. With overhead valves, they were more advanced than the WLA but in the end only 1000-or-so were produced.

Indian meanwhile came out with the 841 (pictured below), which was a V-twin but with the cylinders laid across the frame in the manner of a Moto Guzzi. It stuck with side-valve heads, but like the Harley it was shaft-driven and only 1000 were produced.

At the time, both bikes were built in response for a US Army request for a machine that was intended for desert use. However the decision was made that a Jeep was a far more versatile option. Really good examples of either can hit the $40-50,000 mark.

(H-D pic: Mecum auctions)

****

Premium Brit

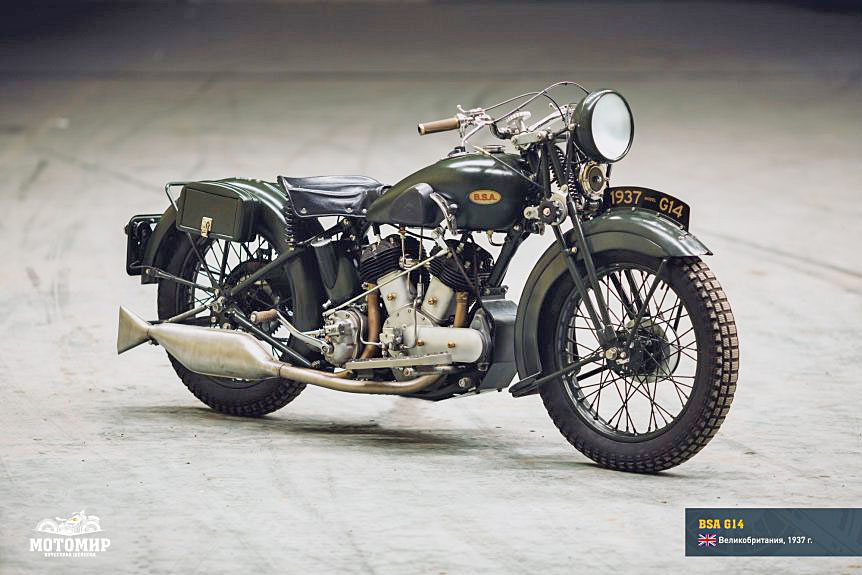

Not all war bikes made it into the big time. A good example is the BSA G14, initially pitched as a premium one-litre road bike designed to handle the stresses of hauling a sidecar.

The 986cc V-twin was a sidevalve claiming 25 horses and was matched to a four-speed transmission

It was a very expensive machine in its day (82 quid, plus speedo!), and is even more so as a collectible now – start thinking $40k-plus. Military versions were sold to several countries, including Holland, Ireland and Sweden. While BSA made literally tens of thousands of singles for military use, only a few thousand of these are thought to have been produced.

(Pic: Motorworld by V.Sheyanov)

****

Ultimate German

For collectors with very deep pockets, the ultimate war prize is a WWII Zundapp KS 750 with sidecar. This and the rival BMW – the R75 – were tested side by side by Wehrmacht command early in 1939 and the Zundapp won. Apparently it was by a substantial margin, to the point where BMW was asked to build the Zundapp instead of its own design.

That went down like the proverbial lead zeppelin and a compromise was reached where BMW gradually modified its design significantly, to the point where it and the Zundapp had numerous parts in common. That had obvious advantages when supplying troops, with fewer parts to source.

Unlike the rival American V-twins, the KS 750 had a more efficient overhead valve engine, also of 750cc capacity. Running 6.2:1 compression, it claimed 26 horses and ran a dual-range four-speed gearbox with shaft final drive.

That shaft had a spline which allowed for a sidecar driveshaft. So with two-wheel-drive and a low range option on the transmission, an outfit could go almost anywhere, despite the weighing 420 kilos. Top speed was 100km/h.

Zundapp is thought to have produced 18,695 of these at Nuremberg up to early 1945, but remarkably few survive. These days, we’re seeing prices ranging from $60k and up.

(Note: a useful info source on Zundapps is online at zundapps.com.)

(Pic: Motorworld by V.Sheyanov)

****

War Bike Resource

One of the more interesting resources we tripped over is a museum in Russia called Motos of War, headed up by a character called Vyacheslav Sheyanov. It’s a privately-owned outfit that specialises in motorcycles from 1930s and 1940s and we’re told it’s well worth a visit. In the meantime you can see it online at motos-of-war.ru.

(Pictured: Benelli M36 circa 1937)

Canadian army newsreel, WWII

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact